P-gp Inhibition: What It Means for Your Medications and How It Affects Your Health

When you take a pill, your body doesn’t just absorb it like water through a sponge. P-gp inhibition, the process where a substance blocks P-glycoprotein, a key transporter that pumps drugs out of cells. Also known as P-glycoprotein inhibition, it can dramatically change how much medicine actually gets into your bloodstream—or how fast it leaves. This isn’t just a lab detail. It’s the reason some pills work better—or worse—when taken with grapefruit juice, turmeric, or even certain probiotics.

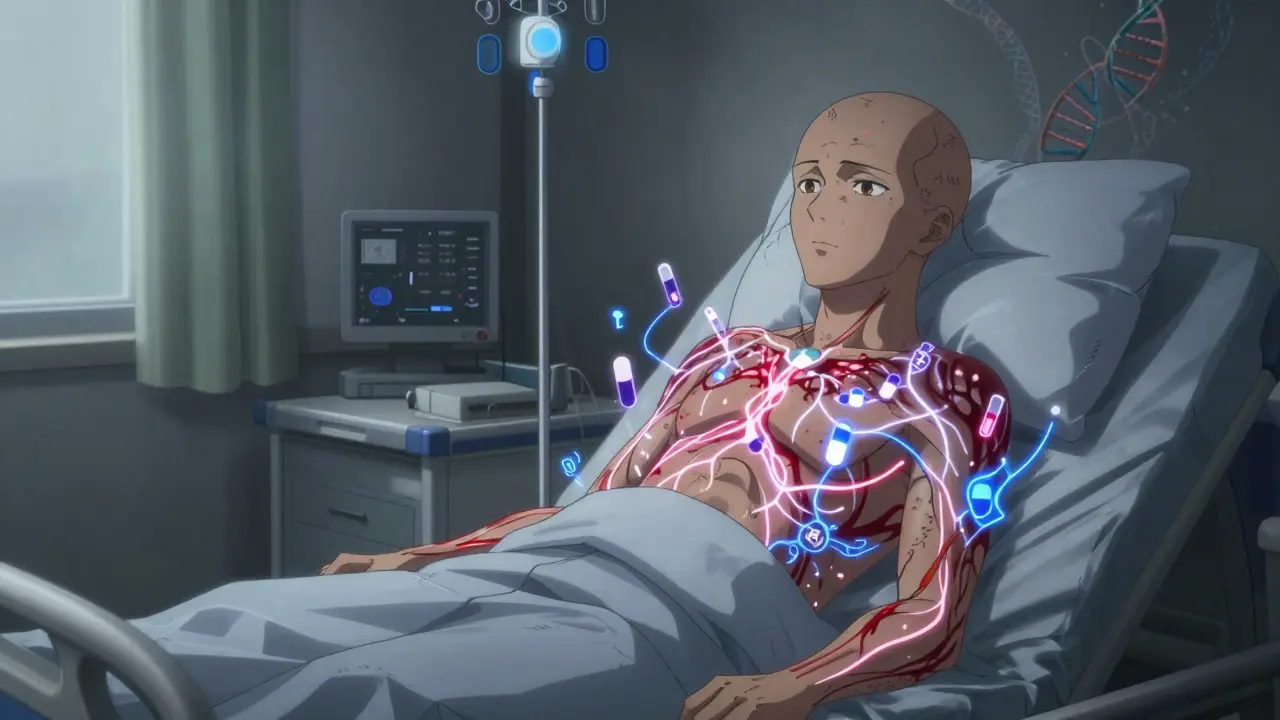

P-gp is like a bouncer at the door of your cells. It kicks out drugs it thinks don’t belong, especially in your gut, brain, liver, and kidneys. When something P-gp inhibition happens, that bouncer gets distracted. Suddenly, more drug slips through. That sounds good—until it’s not. Too much blood concentration of a drug like digoxin, cyclosporine, or even some antidepressants can cause serious side effects. On the flip side, if you’re on a drug that needs to reach the brain, like certain cancer meds, P-gp inhibition might actually help it work better. But that’s a tightrope walk. One study in the Journal of Clinical Pharmacology showed that patients on cyclosporine with added P-gp inhibitors had blood levels spike by over 50%, leading to kidney damage. That’s not a risk you want to guess at.

What causes P-gp inhibition? Common culprits include natural compounds like curcumin in turmeric, quercetin in apples and onions, and even some herbal supplements like St. John’s wort. Even some antibiotics and antifungals can do it. And here’s the kicker: you might not even know you’re taking something that affects it. Many people don’t realize that their daily ginger tea, green tea extract, or even a calcium supplement could be changing how their prescription works. This is why your pharmacist asks about every vitamin and herb you take—even the ones you think are harmless.

It’s not just about what you take—it’s about who you are. Older adults, people with kidney or liver issues, and those on multiple medications are at higher risk. P-gp doesn’t work the same in everyone. Genetics play a role. Age changes it. Other diseases alter it. That’s why a dose that’s safe for one person might be dangerous for another. This isn’t theoretical. It’s why doctors monitor blood levels for drugs like tacrolimus or digoxin so closely when new meds are added.

The posts you’ll find here aren’t just about P-gp inhibition in isolation. They’re about real-world consequences. You’ll see how steroid eye drops like FML Forte might interact with other meds through this pathway. You’ll learn why Medrol and other corticosteroids can cause stomach ulcers—and how P-gp might be involved in how those drugs are processed. You’ll find out how probiotics, ginger, peppermint oil, and even ketoconazole shampoo can quietly change how your body handles medications. These aren’t random topics. They’re all connected by the same invisible system: P-gp.

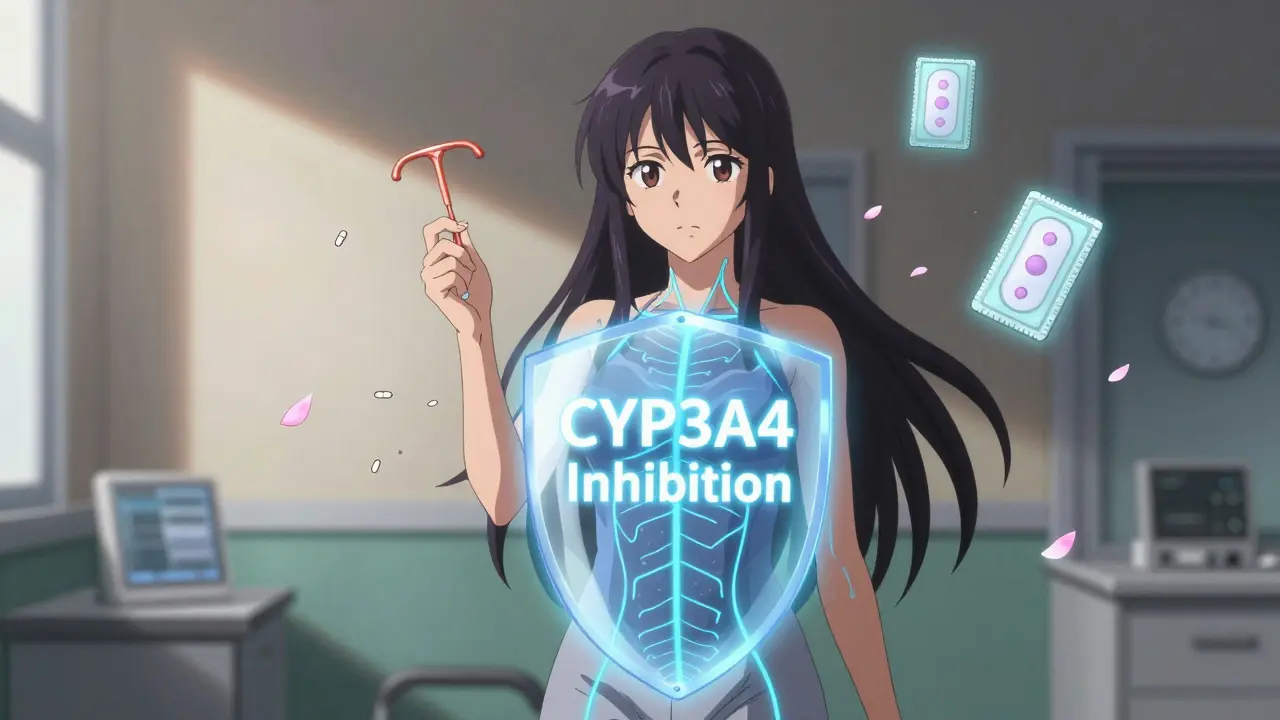

Colchicine and Macrolides: Managing Toxicity from P‑gp and CYP3A4 Inhibition

A deep dive into why colchicine and macrolide antibiotics can be lethal together, how CYP3A4 and P‑gp inhibition raise toxicity, and practical steps to keep patients safe.