Affirmative Consent Laws: What They Really Mean for Medical Decisions

There’s a lot of confusion online about affirmative consent and how it applies to medical care. You might have heard the term in the context of campus policies or #MeToo campaigns and assumed it also governs who can make decisions for you in the hospital. That’s not true. And mixing these two ideas can lead to dangerous misunderstandings-especially when someone is sick, unconscious, or unable to speak for themselves.

What affirmative consent actually means

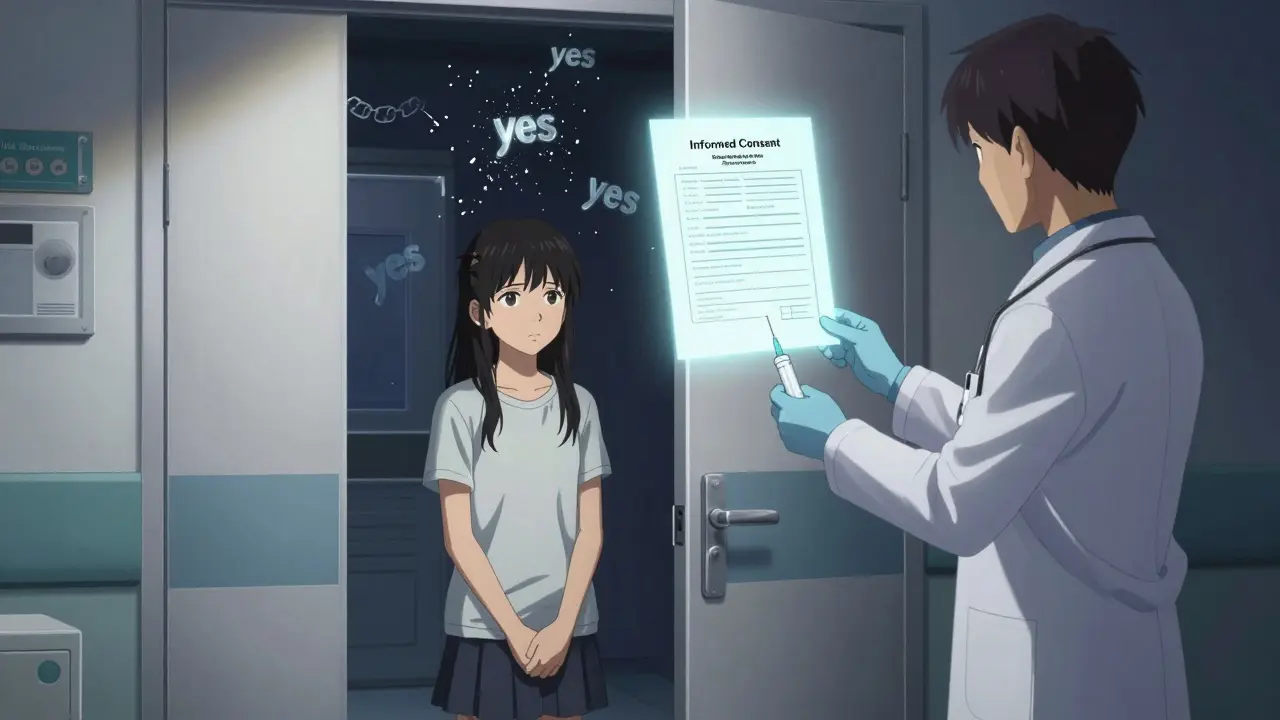

Affirmative consent laws were never designed for medicine. They were created to change how we think about sexual activity. The idea is simple: no means no isn’t enough. You need a clear, enthusiastic, ongoing “yes.” That’s the standard in places like California, New York, and Colorado. It’s about ensuring that every step in a sexual encounter is agreed to, out loud or through clear actions, and that either person can stop at any time. These laws came out of the 2010s, mostly pushed by universities and state legislatures after rising awareness of sexual assault on campuses. California’s Education Code Section 67386, passed in 2014, says consent must be “affirmative, conscious, and voluntary.” That’s it. That’s the whole scope. It applies to relationships between students, staff, and campus visitors. It doesn’t touch medical treatment.Medical consent works completely differently

When you walk into a doctor’s office, the legal standard isn’t affirmative consent. It’s informed consent. That means your doctor has to explain:- What’s wrong with you

- What the treatment does

- What the risks and benefits are

- What other options exist

- What happens if you say no

What happens when you can’t speak for yourself?

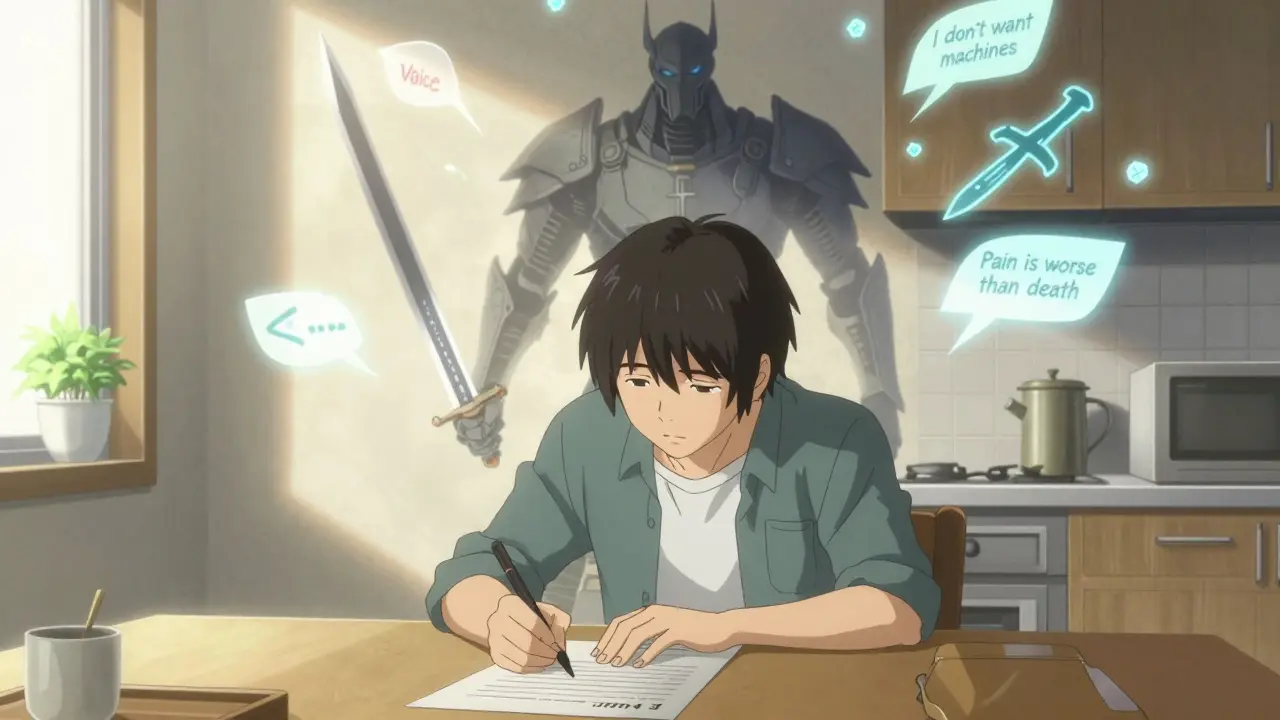

This is where the confusion really starts. People hear “consent” and think it means someone else has to get your verbal okay before acting. But if you’re in a coma, have advanced dementia, or are a child, you can’t give consent. So what happens? The answer is substituted judgment. This isn’t about getting your permission-it’s about figuring out what you would have wanted. A family member or legal guardian steps in, not to decide what’s best for you, but to answer: “What would they have chosen if they could speak?” In California, Health and Safety Code Section 7185 requires surrogates to use this standard. If you’ve written an advance directive-a living will or healthcare power of attorney-that’s the gold standard. If not, the doctor talks to your closest family and asks: “Did they ever say they didn’t want machines? Did they mention religion or quality of life?” This isn’t about enthusiasm. It’s about memory, values, and past statements. It’s not a “yes” you give today. It’s a decision based on who you’ve been.

Why mixing these ideas is dangerous

Some hospitals have tried to apply “affirmative consent” language to medical settings because it sounds ethical. But it doesn’t work. Imagine a patient in the ER after a car crash. They’re unconscious. Their daughter arrives. The doctor says, “Do you give affirmative consent to intubate?” The daughter, terrified and grieving, says nothing. The doctor waits. Silence. No nod. No “yes.” So they don’t intubate. The patient dies. That’s not ethics. That’s legal chaos. In emergencies, there’s no time for ongoing verbal confirmation. The law allows doctors to act under implied consent in life-threatening situations. But if you start treating medical decisions like sexual encounters, you create paralysis. A 2023 advisory from the Federation of State Medical Boards warned exactly this: applying sexual consent standards to medicine “creates unnecessary barriers to urgent care and misunderstands the legal foundations of medical consent.”Who can legally make medical decisions for you?

It depends on your state, but generally, here’s the order:- Someone you named in an advance directive (healthcare proxy)

- Spouse or domestic partner

- Adult children

- Parents

- Siblings

- Close friend (in some states)

What you should do right now

You don’t need to understand every legal term. But you do need to take two simple steps:- Fill out a healthcare power of attorney. Name one person you trust to speak for you if you can’t. Don’t wait until you’re sick.

- Talk to that person. Tell them what matters to you: Do you want to be kept alive on machines? What’s your view on pain management? Have you ever said, “I don’t want to be a burden”? Write those things down. Give them a copy.

What’s changing in 2026?

Nothing. The confusion between medical and sexual consent is still widespread, but the law hasn’t changed. The California Supreme Court ruled in 2023 in Doe v. Smith that affirmative consent laws “apply exclusively to sexual misconduct determinations under Title IX,” not medical care. That decision closed the door on any future attempts to merge the two. Medical organizations like the American Medical Association have doubled down on separating the two. Their 2023 update to Opinion E-2.225 says clearly: “Physicians should not apply sexual consent standards to medical decision-making processes.” The truth is, the systems we have for medical consent-though imperfect-are built on 100 years of legal precedent, ethics, and patient rights. Affirmative consent laws are powerful tools for preventing sexual violence. But they’re not tools for saving lives in the ER.Common misconceptions, cleared up

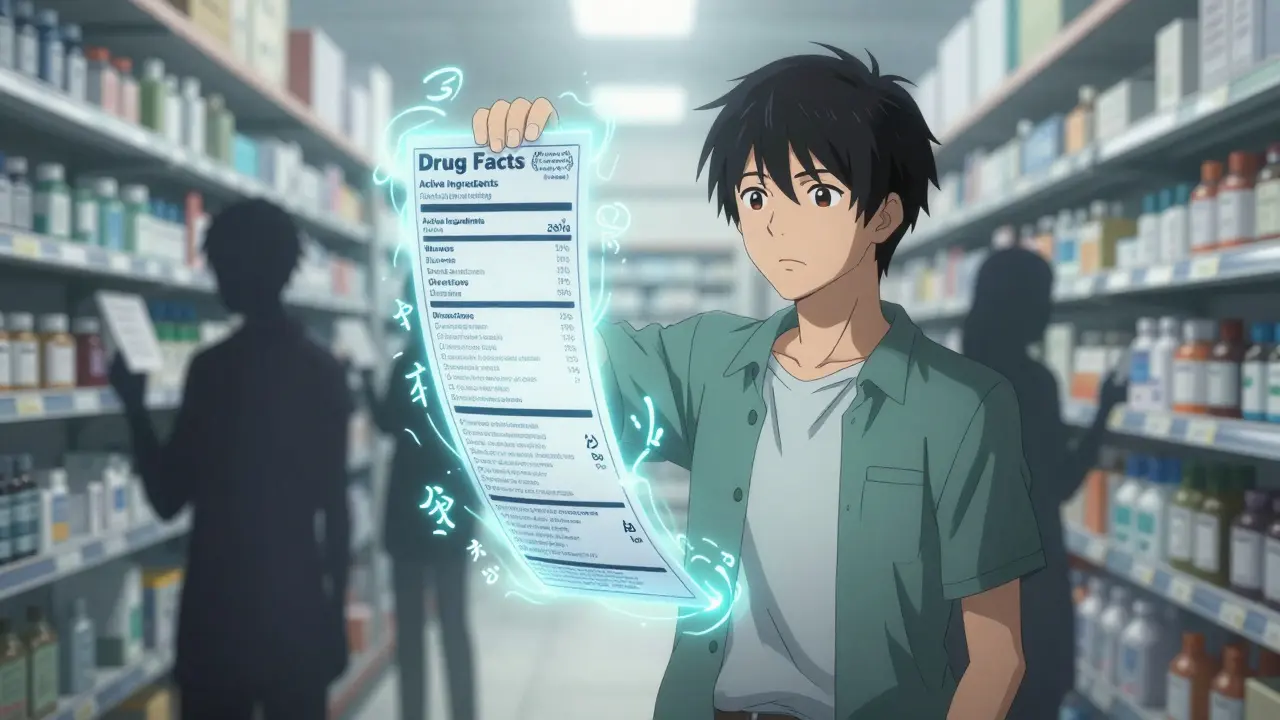

- Myth: You need to say “yes” again for every medical procedure.

Truth: One informed consent covers the whole plan. You don’t re-consent for each needle or scan. - Myth: Family members can override your wishes if they disagree.

Truth: If you have an advance directive, your wishes win-even if your kids think you’re being stubborn. - Myth: Affirmative consent laws apply to all types of consent.

Truth: They apply to sexual activity only. Period. - Myth: If you’re unconscious, doctors can do anything.

Truth: They can only do what’s necessary to save your life. Beyond that, they wait for a surrogate or court order.

Do affirmative consent laws apply to medical treatment?

No. Affirmative consent laws are only about sexual activity. Medical treatment uses informed consent, which requires clear explanations and understanding-not ongoing verbal agreement. Applying sexual consent standards to medicine would delay life-saving care and confuse patients and families.

Can a family member make medical decisions for me without my permission?

Only if you haven’t named someone else. If you’ve completed a healthcare power of attorney, that person has legal authority. If not, state law determines who can speak for you-usually your spouse, adult children, or parents. But they must follow your known wishes, not their own preferences.

What’s the difference between substituted judgment and best interest?

Substituted judgment asks: “What would they have chosen?” It’s based on your past statements, values, or advance directives. Best interest asks: “What would we think is best?” That’s only used if there’s no record of your wishes. Most states require substituted judgment first-it’s more respectful of your autonomy.

Can I refuse treatment even if my family disagrees?

Yes. If you’re conscious and capable, your decision is final-even if your family cries, begs, or threatens to sue. If you’re incapacitated and have an advance directive, your written wishes override family disagreement. Courts rarely override patient autonomy unless there’s evidence the document is invalid.

Why do some hospitals use “yes means yes” language in medical forms?

Some institutions mistakenly think it sounds more ethical or modern. But it’s legally incorrect and practically harmful. Medical consent doesn’t require enthusiasm-it requires understanding. Using sexual consent language in healthcare settings confuses patients, delays care, and exposes hospitals to liability. Major medical groups have warned against this practice.

Comments

Gary Mitts

February 1, 2026 AT 18:23So let me get this straight-some hospital is gonna wait for a nod before sticking a tube in a dying person? 😂

Bridget Molokomme

February 2, 2026 AT 11:42Yup. And then the family sues because ‘they didn’t say yes loud enough.’

Meanwhile, the patient is dead. Classic.

jay patel

February 4, 2026 AT 02:01Man this is wild. I live in India and we dont even have proper consent forms in most rural hospitals but people still trust doctors. Here in US you got lawyers writing scripts for every IV push. Affirmative consent for sex? Cool. For surgery? Bro, you gonna make a whole TED Talk before they stitch you up? 😅

And dont even get me started on the ‘enthusiastic yes’ for a coma patient. Like, what, they gotta wink? 😂

Hannah Gliane

February 5, 2026 AT 15:55OMG I KNEW IT 😤

Of COURSE some woke hospital is misapplying this. I work in ER. Last week a nurse asked a grieving daughter ‘Are you giving affirmative consent?’ like it was a Tinder match. The woman just cried and said ‘Just fix him!’

Then the doctor had to explain it’s not a dating app. I swear, woke culture is killing people.

😭

Murarikar Satishwar

February 7, 2026 AT 14:24Actually, the legal framework around medical consent is one of the most mature systems in the world. Informed consent has been refined over a century of jurisprudence, ethical debate, and patient advocacy. It’s not perfect, but it balances autonomy with practicality. Affirmative consent in sexual contexts is a necessary cultural shift-but transplanting it into medicine is like using a hammer to thread a needle. The tools are designed for different jobs. Misapplying them doesn’t make you progressive-it makes you dangerous.

Dan Pearson

February 7, 2026 AT 23:19THIS IS WHY AMERICA IS FALLING APART. You want to protect people? Then stop turning every medical decision into a performance art piece. We’re not in a college dorm. We’re in an ER. Someone’s bleeding out. They don’t need a consent form with emojis. They need a surgeon.

And if you think California’s laws are the gold standard, you’ve never seen a real emergency. We don’t need woke bureaucrats telling doctors how to save lives. We need competence. Not consent theater. 🇺🇸🔥

Bob Hynes

February 9, 2026 AT 09:41Man I love how Canada just says ‘Do what’s needed’ and moves on. We got a guy in our ER last year who was unconscious from a bike crash. Docs intubated him. Family showed up 20 mins later. They were grateful. No forms. No ‘enthusiastic yes.’ Just care.

Maybe we’re just… less dramatic? 😅

Also, I think Americans confuse ‘ethical’ with ‘performative.’

Brett MacDonald

February 10, 2026 AT 09:31It’s funny how we’ve turned autonomy into a ritual. Consent isn’t about words-it’s about agency. But when you demand verbal confirmation in a crisis, you’re not honoring autonomy-you’re replacing it with performative compliance. The real question isn’t ‘Did they say yes?’

It’s ‘Did they ever get to choose?’

And that’s why advance directives matter more than any slogan.

Sandeep Kumar

February 11, 2026 AT 14:12Why do Americans make everything so complicated? In India we just say ‘Doctor, do what you think is right.’ And they do. No paperwork. No legal jargon. Just trust.

Now you want someone to say ‘yes’ before giving CPR? Bro, you’re not saving lives-you’re running a courtroom.

And you wonder why healthcare is expensive?

clarissa sulio

February 13, 2026 AT 02:17I’ve seen this happen. A woman in the ICU had a living will saying NO machines. Her kids ignored it. Hospital hesitated. They waited for ‘consent.’ She died waiting for them to get their paperwork right.

Don’t confuse bureaucracy with ethics. This isn’t about rights-it’s about responsibility.

Monica Slypig

February 13, 2026 AT 08:52Of course the system is perfect. It’s just that people are too stupid to understand it. Why do you think we need to explain this in a 5000-word post? Because the average person thinks ‘consent’ means ‘say yes every 10 seconds.’

And now they’re suing hospitals for not asking for a verbal high-five before intubating.

Someone please tell me why we’re still paying for this.

Becky M.

February 14, 2026 AT 08:41Thank you for writing this. I’m a nurse and I’ve seen families panic because they think they need to ‘agree’ to every test. I always say: ‘You don’t need to say yes-you just need to understand.’

And if you don’t understand? We’ll slow down. But we won’t stop.

Also, please fill out your advance directive. It’s not morbid. It’s love.

And yes, I’ve sent 30 people to the website today. You’re welcome.