Opioids During Pregnancy: Risks, Withdrawal, and Monitoring

When a pregnant person is using opioids - whether prescribed for pain or used as part of an opioid use disorder - the stakes aren’t just about their own health. The baby’s life, too, hangs in the balance. The good news? We now know how to manage this safely. The bad news? Too many still don’t get the care they need.

Why Opioid Use in Pregnancy Is Different

Opioids cross the placenta. That means whatever the mother takes, the baby gets too. It’s not about willpower or choice. It’s about biology. When a pregnant person stops opioids suddenly - even under medical supervision - the baby goes into withdrawal too. That’s called Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome (NOWS), or sometimes Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS). And it’s not rare. Between 50% and 80% of babies exposed to opioids in the womb will show signs of withdrawal after birth.The Only Safe Way: Medication-Assisted Treatment

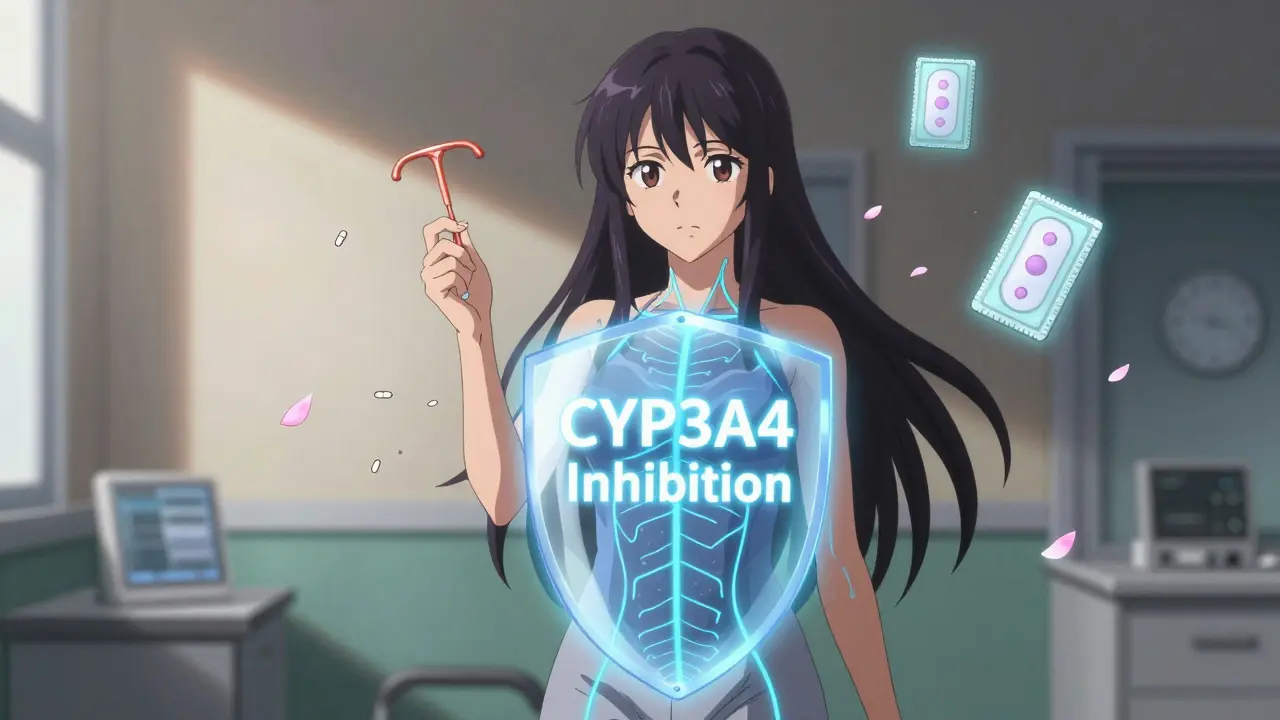

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the CDC, and the American Society of Addiction Medicine all agree: medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is the standard of care. That means using methadone or buprenorphine to stabilize the mother’s system - not to get high, but to prevent withdrawal, reduce cravings, and keep her in treatment. Methadone has been used for decades. Dosing starts low - around 10 to 20 mg a day - and is slowly increased until the person feels stable, usually between 60 and 120 mg daily. Buprenorphine, a newer option, starts at 2 to 4 mg sublingually and can be increased up to 24 mg daily. Both are safe during pregnancy. Neither causes birth defects. Neither increases the risk of miscarriage. What’s the alternative? Medically supervised withdrawal. It sounds logical. But it doesn’t work. Studies show that 30 to 40% of people who try to quit opioids cold turkey during pregnancy relapse. And relapse means higher risks: preterm labor, fetal distress, even stillbirth. The CDC says withdrawal increases the chance of preterm birth from 15-20% to 25-30%. That’s not a risk worth taking.What Happens to the Baby?

NOWS symptoms usually show up 48 to 72 hours after birth. The baby might be jittery, cry nonstop, have trouble feeding, sweat, have a high fever (over 37.2°C), or breathe faster than 60 times a minute. They might have loose stools more than three times an hour. These aren’t signs of neglect - they’re signs of physiology. Hospitals use scoring systems like the Finnegan scale to measure severity. A score of 8 or higher often means medication is needed. But here’s the thing: not all babies need drugs. The Eat, Sleep, Console model - now used in over 650 U.S. hospitals - focuses on keeping the baby calm, feeding often, and holding them close. When this works, it cuts the need for morphine or methadone treatment by 30 to 40%.

Methadone vs. Buprenorphine: What’s Better?

Both work. But they have different trade-offs. Methadone keeps more mothers in treatment - 70 to 80% stay in care after six months. But babies exposed to methadone tend to have worse withdrawal. Their hospital stays average 17.6 days. Their Finnegan scores are higher, around 14.3 on average. Buprenorphine? Babies usually have milder symptoms - average Finnegan score of 11.8 - and shorter stays, around 12.3 days. But only 60 to 70% of mothers stay in treatment long-term. And about 46% of these babies still need medication to manage withdrawal. Then there’s naltrexone. It’s not an opioid. It blocks opioids. In a 2022 Boston Medical Center study, babies exposed to naltrexone had a 0% rate of NOWS. Zero. They went home in two days. Moms were more likely to breastfeed successfully. But here’s the catch: these moms started treatment later - at 28.4 weeks on average - compared to 19.7 weeks for those on buprenorphine. That’s a problem. Starting late means more risk to the baby during the first half of pregnancy.What About Breastfeeding?

Yes, you can breastfeed while on methadone or buprenorphine. The amount that passes into breast milk is tiny - far less than what the baby was exposed to in the womb. In fact, breastfeeding can actually help reduce withdrawal symptoms. The American Academy of Pediatrics says it’s encouraged unless the mother is HIV-positive or using other unsafe drugs. One mother on a recovery forum wrote: “I was scared to nurse. But my baby slept better, cried less. We both healed faster.” That’s not anecdotal. It’s backed by data.Why So Many Are Still Left Behind

Despite all this, only 45% of U.S. hospitals have standardized protocols for treating opioid use disorder in pregnancy. In rural areas, that number drops to 28%. Many clinics don’t have buprenorphine on site. Some don’t even know how to prescribe it. And stigma? It’s real. One mother shared on Reddit: “The nurse said, ‘You’re lucky you didn’t lose the baby.’ Like I wanted this. Like I chose it.” That kind of judgment makes people hide. It makes them skip appointments. It makes them relapse.

New Hope: Extended-Release Options

In 2023, the FDA approved Brixadi - an extended-release form of buprenorphine given as a weekly or monthly injection. Early data shows 89% of pregnant women stayed in treatment at 24 weeks, compared to 76% with daily pills. That’s huge. Fewer missed doses. Less stress. More stability. The NIH’s HEALing Communities Study is testing integrated care - combining MAT, mental health support, housing help, and transportation - across 67 sites. Early results? A 22% drop in NAS severity when all pieces are in place.What You Need to Do

If you’re pregnant and using opioids:- Don’t stop cold turkey. Talk to a provider who understands addiction medicine.

- Ask about buprenorphine or methadone. These are safe and effective.

- Start treatment as early as possible - ideally by 8 to 12 weeks.

- Find a care team that includes an OB, an addiction specialist, and a pediatrician.

- Ask about the Eat, Sleep, Console approach for your baby after birth.

- Don’t be afraid to breastfeed. It helps.

What’s Next?

The rise in NAS cases - up fivefold from 2010 to 2020 - isn’t just a medical issue. It’s a social one. Nearly half of pregnant women with opioid use disorder are homeless or housing insecure. One in three has depression. One in two has trauma history. Treating the addiction isn’t enough. You have to treat the person. That means housing. Childcare. Therapy. Transportation. Legal help. Medicaid coverage for MAT is required by federal law since 2020 - but only 32 states fully follow through. That’s unacceptable. The tools exist. The science is clear. What’s missing is the will to make care accessible, compassionate, and available to everyone - no matter where they live, what they’ve done, or how they got here.Is it safe to take methadone or buprenorphine while pregnant?

Yes. Both methadone and buprenorphine are safe and recommended during pregnancy. They reduce the risk of miscarriage, preterm birth, and fetal distress compared to stopping opioids suddenly. These medications stabilize the mother’s system, improve prenatal care adherence, and lead to healthier birth outcomes, including higher birth weight and longer gestation.

Will my baby be born addicted to opioids?

Babies born to mothers on methadone or buprenorphine aren’t addicted - they’re physically dependent, which is different. This means their bodies have adapted to the medication and may show withdrawal symptoms after birth, known as Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome (NOWS). It’s treatable, not a lifelong condition. Most babies recover fully with proper care.

Can I breastfeed if I’m on opioid treatment?

Yes. The amount of methadone or buprenorphine that passes into breast milk is very low - far less than what the baby was exposed to during pregnancy. Breastfeeding can actually reduce the severity of withdrawal symptoms and help your baby bond with you. The American Academy of Pediatrics supports breastfeeding for mothers on these medications, unless they have HIV or are using other unsafe substances.

What if I can’t afford treatment?

The 2020 SUPPORT Act requires Medicaid to cover medication-assisted treatment for pregnant women. All 50 states and D.C. are required to provide this coverage. If you’re being denied care, contact your state’s Medicaid office or a local maternal health advocate. Many clinics offer sliding-scale fees or free services regardless of insurance status.

How long will my baby stay in the hospital?

It depends. Babies on methadone may stay 14 to 20 days, while those on buprenorphine often go home in 7 to 12 days. If the hospital uses the Eat, Sleep, Console approach, many babies go home even sooner - sometimes within 48 hours - without needing medication. The key is consistent monitoring and non-drug care like skin-to-skin contact, quiet rooms, and frequent feeding.

Are there alternatives to methadone and buprenorphine?

Naltrexone is an option, but it’s not first-line. It blocks opioids and doesn’t cause withdrawal in babies - but it’s only effective if the mother has been opioid-free for 7 to 10 days before starting. That’s hard to do during pregnancy, and starting late increases risks. Most experts recommend methadone or buprenorphine because they’re safer to start early and easier to maintain.

What if I’m already in withdrawal?

Don’t wait. Call a provider immediately. You can start buprenorphine even if you’re in mild withdrawal - as long as you’re not using other opioids. Clinics use the Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale (COWS) to assess severity. If you’re scoring 8 or higher, treatment can begin. Delaying care puts both you and your baby at greater risk.

Can I get help if I live in a rural area?

Yes. Telehealth now allows many pregnant women to access addiction specialists remotely. Some rural clinics partner with urban hospitals to provide MAT through mobile units or telemedicine. The National Rural Health Association is working to expand access. If you’re struggling to find care, call the SAMHSA helpline at 1-800-662-HELP - they can connect you to local resources.

Comments

Ryan Everhart

November 14, 2025 AT 00:45So let me get this straight-we’re giving pregnant people methadone to avoid withdrawal, but we’re not giving them housing, childcare, or therapy? That’s not treatment. That’s damage control with a side of virtue signaling.

Alex Ramos

November 15, 2025 AT 16:57This is one of the most clear-headed pieces I’ve read on this topic. Seriously. The Eat, Sleep, Console model is a game-changer. My cousin’s baby was on buprenorphine and only stayed 5 days-no meds, just skin-to-skin and feeding every 2 hours. 🙌

Erica Cruz

November 15, 2025 AT 18:47Wow. So we’re now medicalizing addiction like it’s a chronic illness instead of a moral failure? Next they’ll tell us to give out free IV drips of empathy.

Benjamin Stöffler

November 15, 2025 AT 19:36Let’s be precise: the notion that MAT is ‘safe’ is a semantic sleight-of-hand. The fetus is still pharmacologically dependent-this isn’t safety, it’s harm reduction dressed in white coats. The real question isn’t whether methadone works-it’s whether we’ve normalized chemical tethering as a reproductive right.

And let’s not pretend the Finnegan scale is objective-it’s a behavioral proxy for physiological stress, and yet we treat it like a diagnostic gold standard. Where’s the neuroimaging? The epigenetic markers? The longitudinal studies beyond 2 years?

The ‘Eat, Sleep, Console’ model sounds charmingly pastoral, but it assumes a stable home environment, a non-addicted caregiver, and a hospital with adequate staffing-all luxuries in rural Appalachia or the South Bronx.

And naltrexone? Zero NOWS? That’s not a miracle-it’s a selection bias. These women started at 28 weeks because they were already detoxed. That’s not a population-level solution-that’s cherry-picking the low-hanging fruit.

The 89% retention rate with Brixadi? That’s because it’s injectable. No daily pill, no clinic visits, no stigma. But we’re still not addressing the trauma, the poverty, the intergenerational neglect that got them here in the first place.

And breastfeeding? Of course it helps. Oxytocin is a natural analgesic. But the assumption that all mothers want to breastfeed ignores the reality that many are coerced, shamed, or too medicated to hold their babies.

And don’t get me started on Medicaid coverage. It’s mandated by law, yes-but only if you’re not in a state that refuses to expand it. And even then, the reimbursement rates are so low that clinics won’t take it.

We’re treating symptoms like they’re the disease. We’re giving pills instead of purpose. We’re giving protocols instead of power.

This isn’t public health. It’s triage with a PowerPoint.

Amie Wilde

November 16, 2025 AT 18:00My sister did buprenorphine and breastfed. Baby was home in 3 days. No drama. Just love, food, and quiet.

Alyssa Lopez

November 17, 2025 AT 15:26So now we’re giving addicts meds to keep them from overdosing on their own kids? That’s the new pro-life? You’re not saving babies-you’re just making sure they’re born into the system. Medicaid will pay for the NICU stay, but not the daycare. The system’s rigged.

Chrisna Bronkhorst

November 18, 2025 AT 21:52The data on buprenorphine vs methadone is solid but the real issue is access. In 2024, a pregnant woman in rural Mississippi still has to drive 90 miles to get a script. Meanwhile, the DEA limits buprenorphine prescribers to 100 patients per provider. That’s not policy. That’s bureaucratic cruelty.

edgar popa

November 19, 2025 AT 14:19you dont have to be perfect to be a good mom. just be present. and ask for help. you got this 💪

Esperanza Decor

November 20, 2025 AT 16:31I work in a rural OB clinic and we just started offering telehealth MAT last month. One mom cried when she got her first buprenorphine script because the last time she tried to get help, the nurse told her she was a ‘bad mother’ and to ‘just quit.’ We’re not just prescribing meds-we’re rebuilding trust. One appointment at a time.

Gary Hattis

November 22, 2025 AT 14:43As a Black dad in Atlanta, I’ve seen this play out. The same woman who gets buprenorphine in the hospital gets her baby taken by CPS the next day because the social worker ‘didn’t trust her stability.’ We need policy that doesn’t punish survival.

Shante Ajadeen

November 23, 2025 AT 22:18thank you for writing this. i was scared to tell anyone i was on methadone. reading this made me feel less alone.

Deepa Lakshminarasimhan

November 23, 2025 AT 22:54they’re using this to track you. the buprenorphine has a chip. they’re building the database for the next phase. you think they care about babies? they care about control. the CDC isn’t helping-they’re harvesting data.

Johnson Abraham

November 24, 2025 AT 16:24so if you’re preggo and on heroin, just take a pill? that’s it? no rehab? no counseling? just swap one drug for another? sounds like a scam.

David Barry

November 25, 2025 AT 17:26Let’s not confuse correlation with causation. The drop in NAS severity with integrated care? That’s because the women in the NIH study had case managers, Uber rides, and free childcare. Not the medication. The medication is a placebo. The real intervention is social support. Which we don’t fund. Because it’s cheaper to pay for a 17-day NICU stay than a $10,000 housing voucher.

Eve Miller

November 26, 2025 AT 22:37It is unconscionable that any medical professional would ever suggest that opioid use during pregnancy is anything other than child endangerment. The fact that we are normalizing this as ‘treatment’ rather than criminal negligence is a moral collapse.