Why Generic Drug Prices Vary So Much Between U.S. States

Have you ever filled a prescription for a generic drug and been shocked by the price-only to find out your friend in another state paid a third of what you did? It’s not a mistake. It’s not a glitch. It’s the reality of how generic drug pricing works in the U.S. The same pill, made by the same factory, sold in the same dose, can cost three times more in one state than another. And the reasons? They’re not about quality, supply, or demand. They’re about hidden systems, legal loopholes, and who’s pulling the strings behind the scenes.

Why the Same Drug Costs More in Some States

Generic drugs are supposed to be cheap. After all, they’re copies of brand-name drugs that have lost patent protection. The whole point is to slash prices. But here’s the catch: the price you pay at the pharmacy isn’t the price the pharmacy pays. It’s not even the price the manufacturer charges. It’s a tangled web of middlemen, contracts, and state-level rules that nobody talks about.

In California, a 90-day supply of generic atorvastatin (the cholesterol drug) might cost $45 with insurance. In Texas, the same prescription could cost $120. Why? Because each state has different rules for how Medicaid and private insurers reimburse pharmacies. Some states use the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC), which updates monthly and reflects what pharmacies actually pay. Others use outdated benchmarks that don’t match reality. That gap? That’s where prices balloon.

The Hidden Players: PBMs and Their Game

Behind almost every price difference is a Pharmacy Benefit Manager-or PBM. These companies act as middlemen between drug manufacturers, insurers, and pharmacies. They negotiate prices, set formularies, and collect rebates. But here’s the problem: their business model isn’t built on lowering costs. It’s built on obscuring them.

PBMs often get paid through spread pricing. That means they tell your insurer the drug costs $100. They tell the pharmacy they’ll pay $60. They pocket the $40 difference. And because most states don’t require transparency about these spreads, you never see it. A 2022 study from the USC Schaeffer Center found that U.S. consumers overpay for generics by 13% to 20% because of these hidden markups. And it’s worse in states with weak oversight.

States like Vermont and California passed laws requiring PBMs to disclose their pricing practices. In those states, patients pay 8-12% less on average. But in states with no such laws, PBMs operate in the dark. And they profit from that darkness.

Cash vs Insurance: The Real Savings Secret

Here’s one of the biggest surprises: if you’re paying for a generic drug with insurance, you’re often paying more than if you paid cash.

Why? Because your insurance plan has a contract with a PBM that sets your copay. But that copay isn’t based on the actual cost of the drug-it’s based on the PBM’s negotiated rate, which may be inflated. Meanwhile, pharmacies that accept cash payments-like Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company or Blueberry Pharmacy-buy drugs directly from manufacturers and charge a flat markup. No middlemen. No spreads. No hidden fees.

GoodRx data from 2022 showed that for the same generic drug, cash prices were 30% to 70% lower than insurance copays. And in states with fewer pharmacies, like rural areas of Nebraska or West Virginia, the cash savings can be even bigger. That’s why 4% of all generic prescriptions in 2020 were paid in cash-97% of those were for generics. People figured it out. They just needed a way to find the price.

State Laws: Some Help, Some Backfire

States have tried to fix this. Maryland passed a law in 2017 that capped generic drug prices to prevent “price gouging.” It worked-for a while. Then a federal court struck it down, saying states can’t regulate prices that cross state lines. Nevada tried targeting diabetes drug prices. The lawsuit was dropped. Why? Because manufacturers and PBMs threatened to sue under the Defend Trade Secrets Act, claiming the state was stealing their pricing data.

So now, states are shifting tactics. Instead of setting price caps, they’re pushing for transparency. California requires PBMs to report their spreads. New York mandates that pharmacies tell you the cash price before you pay. These aren’t perfect fixes, but they give consumers tools to fight back.

Meanwhile, 18 states have created drug affordability boards as of 2023. These panels review drug prices and recommend action. But they can’t force anyone to lower prices. They’re advisory. And they’re slow. So while they look good on paper, they don’t stop your prescription from costing $150 this month.

Medicare’s Cap Doesn’t Fix Everything

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 capped insulin at $35 a month and will cap total out-of-pocket drug spending at $2,000 a year starting in 2025. Sounds great, right? But here’s the catch: it only applies to Medicare Part D beneficiaries. That’s about 32% of U.S. drug spending.

If you’re under 65 and get insurance through your job, you’re not covered. If you’re on Medicaid, your state’s rules still apply. If you’re uninsured, you’re on your own. And even for Medicare patients, the cap doesn’t touch the underlying price differences between states. You might pay $35 for insulin, but if your blood pressure pill costs $80 in Florida and $25 in Minnesota, you’re still stuck with the gap.

What You Can Do Right Now

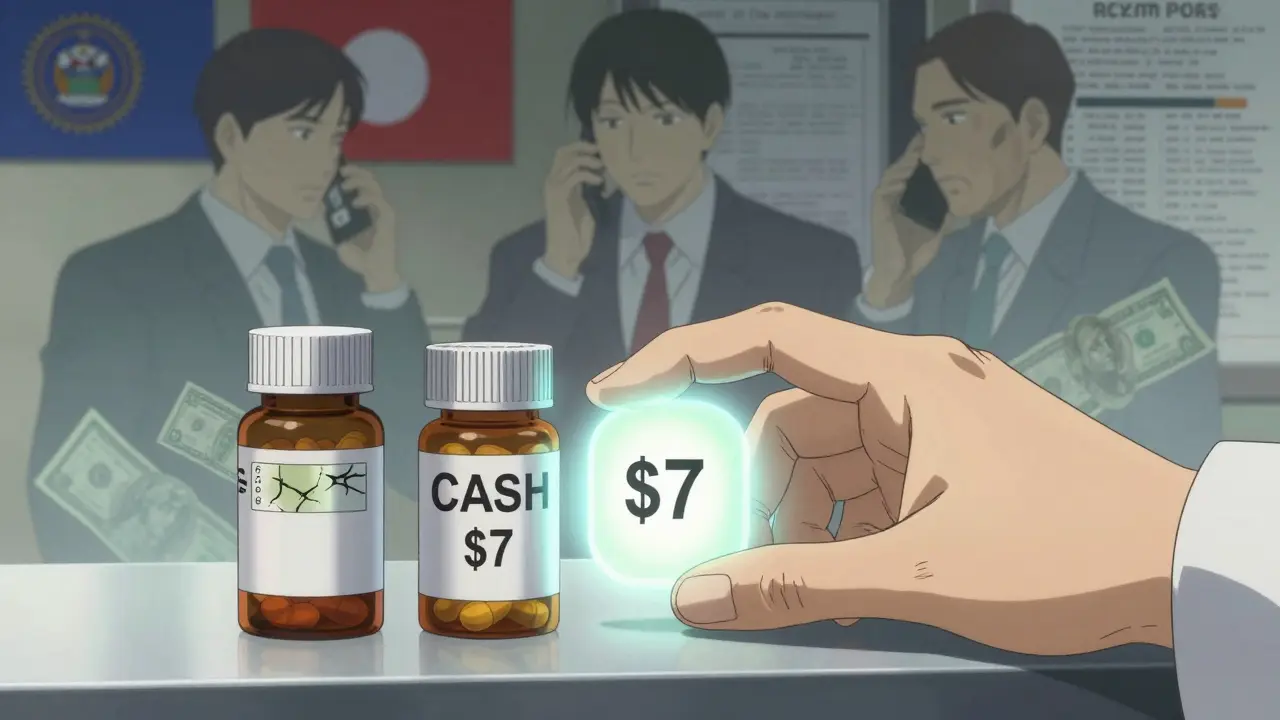

Don’t wait for your state to fix this. You can take control today.

- Always ask for the cash price before using insurance.

- Use GoodRx, SingleCare, or RxSaver to compare prices at nearby pharmacies.

- If your pharmacy doesn’t list cash prices, call other pharmacies in your area. Prices can vary by 50% within the same city.

- Switch to a cash pharmacy if your state has one. These pharmacies often charge 70% less than insurance copays.

- Check if your state has a drug affordability board or transparency law. If so, use their price lookup tools.

For example, in Ohio, a 30-day supply of metformin might cost $18 with insurance. But the cash price at a local pharmacy is $7. That’s not a typo. That’s the system working as designed-for someone else’s profit.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Keeps Happening

Generic drugs make up 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. But they account for only 18% of total drug spending. That means the system isn’t broken because generics are expensive. It’s broken because the middlemen are making money off how they’re priced.

The U.S. spends 2.78 times more on prescription drugs than other wealthy countries. And state-by-state variation is part of why. While Canada or Germany have national pricing systems, the U.S. lets each state-and each PBM-set its own rules. The result? A patchwork of unfairness.

And here’s the worst part: the companies making billions from this system aren’t drugmakers. They’re the PBMs, the insurers, and the pharmacy chains that benefit from opacity. The manufacturers? They’re often selling generics for pennies. The real gouging happens downstream.

Until states enforce real transparency-or Congress steps in with federal price standards-this won’t change. But until then, you have more power than you think. Know your options. Shop around. Pay cash when it makes sense. And don’t assume your insurance is helping you. Sometimes, it’s the reason you’re paying so much.

Comments

Maddi Barnes

February 19, 2026 AT 06:58Okay but like… have you ever tried to fill a script in rural Texas? 😩 I paid $140 for metformin last month. My cousin in Oregon paid $9. Same pill. Same pharmacy chain. Same day. The PBM just… decided I was worth less? 🤡

And don’t even get me started on how insurance ‘copays’ are just fancy word games. I’ve had my plan say ‘$40 copay’… then later bill me $200 because ‘the PBM adjusted the rate.’ Adjusted?! Adjusted from what?! The truth? That’s the real drug.

I started using GoodRx. Cash price? $5.50. I cried. Not from joy. From rage. This system is a horror show with a spreadsheet.

Also, why does every state have different rules? We’re one country. We have one FDA. Why are we playing Monopoly with people’s health? Someone’s making bank while we’re all scrambling to afford insulin. It’s not capitalism. It’s feudalism with a pharmacy counter.

I’m not even mad. I’m just… disappointed. Like, I used to believe in America. Now I believe in cash.

Benjamin Fox

February 20, 2026 AT 14:53WTF is this liberal nonsense? You think the government should fix prices? Nah. Let the market work. If you’re paying too much go to Mexico. Or Canada. Or China. Or whatever. Stop crying. People in Europe pay more for healthcare and they don’t even have good coffee. You’re just mad because you don’t want to take responsibility.

Also why is everyone using GoodRx? That’s just a middleman too. You’re just trading one scam for another. I pay cash. I buy in bulk. I don’t need your pity. 🇺🇸

Jonathan Rutter

February 22, 2026 AT 11:39Let me tell you something you’re not hearing from the mainstream media. PBMs aren’t the problem. They’re the symptom. The real villain? The FDA. They let 12 different manufacturers make the same generic drug but call it ‘bioequivalent’ like that means anything. One pill has 3% more filler. Another has 7% less active ingredient. But hey - they’re ‘the same’.

And don’t even get me started on how pharmacies get paid. They’re incentivized to push higher-priced drugs because the rebate is bigger. So if you’re on insurance? You’re being manipulated into paying more. The pharmacist knows. They just smile and say ‘Your copay is $40.’

I’ve worked in pharmacy for 18 years. I’ve seen people cry because they had to choose between their blood pressure meds and groceries. And no one in Congress gives a damn. They’re all on the PBM payroll. Literally. Campaign donations. Lobbying. It’s all connected.

You think California’s law helped? Nah. PBMs just moved their HQs to Delaware. They still pocket the spread. They’re not even trying anymore. They just print money and laugh.

And you? You’re still using insurance. You’re still not asking for the cash price. You’re still letting them win. Wake up. It’s not a system. It’s a pyramid scheme with a white coat.

Jana Eiffel

February 24, 2026 AT 11:21It is both a moral and economic paradox that a nation which prides itself on innovation and market efficiency permits such egregious disparities in the cost of essential therapeutics. The absence of a unified pricing mechanism reflects not merely regulatory fragmentation, but a profound failure of collective ethical stewardship.

One cannot reasonably assert that the pharmaceutical supply chain operates under principles of transparency when the very entities entrusted with cost containment-Pharmacy Benefit Managers-function as black-box intermediaries, profiting from obfuscation. The notion that a 30-day supply of metformin can vary from $5 to $150 across contiguous geographies is not a market phenomenon; it is a systemic betrayal.

Furthermore, the reliance on cash-based alternatives, while pragmatically rational, imposes an undue burden upon those without liquidity, perpetuating health inequities along socioeconomic lines. The solution is not individual consumer vigilance, but structural reform: federal price transparency mandates, elimination of spread pricing, and the integration of a national reference pricing database.

Until then, we are not patients-we are data points in a profit algorithm.

John Cena

February 24, 2026 AT 18:52I’ve been reading this whole thing and honestly… I’m just tired. Like, I get it. It’s messed up. But what can one person do? I’m on a tight budget. I work two jobs. I don’t have time to call five pharmacies every time I need a script.

I use GoodRx now. It saved me $120 on my thyroid med. I didn’t even know that was possible. But I still feel guilty. Like I’m gaming the system. Like I’m supposed to just suffer and be grateful.

Maybe we need more than just apps. Maybe we need to vote. Maybe we need to talk to our reps. Maybe we need to stop treating healthcare like a shopping mall.

Anyway. Thanks for writing this. I didn’t know half this stuff. Now I do. And I’m not going to ignore it anymore.

aine power

February 25, 2026 AT 00:28Metformin costs $5? How quaint. I pay $2.50 at CVS. I don’t use apps. I don’t care about PBMs. I’m on Medicare. I have a personal pharmacist. I’m not one of you.

Also, ‘cash price’? That’s for peasants.

Tommy Chapman

February 25, 2026 AT 01:28Stop whining. If you can’t afford your meds then don’t take them. Simple. You want free stuff? Go live in Sweden. But don’t come crying to me because you’re too lazy to work overtime or get a side gig. I work 60 hours a week and I still pay full price for my meds. No pity. No handouts. You want cheaper drugs? Then stop letting the government run everything.

Also, GoodRx? That’s just a scam. They sell your data. You think you’re saving money? You’re just giving PBMs more info on how to screw you next time.

And yeah I said it. You’re weak. Get tough. Or shut up.

Irish Council

February 26, 2026 AT 04:11Did you know the FDA approves generics from factories in India that have never been inspected? And the PBM contracts are signed in offshore shell companies? And the state Medicaid systems use outdated NADAC because they’re too broke to update them? This isn’t a pricing issue. It’s a controlled demolition of public health.

They’re not just profiting. They’re creating dependency. The more you rely on insurance, the more you’re trapped. The cash option? That’s the only way out. But they don’t want you to know that.

They want you to believe it’s your fault you’re paying too much. It’s not. It’s a war. And you’re the casualty.

Freddy King

February 26, 2026 AT 14:31Let’s break this down like a clinical trial. PBMs = intermediaries. Spread pricing = revenue model. State-level reimbursement = heterogenous benchmarks. Cash pricing = direct-to-consumer disruption. The variance in price isn’t noise-it’s signal. And the signal is: profit extraction is optimized where oversight is minimal.

Meta-analysis of 2022 USC data shows 17.3% average overpayment. That’s not a bug. It’s a feature. The system is designed to extract surplus value from uninsured and underinsured populations. The fact that you’re surprised? That’s the primary outcome of decades of opacity.

And yes-cash is king. But only if you have the liquidity. Which brings us to structural inequality. So congrats. You’ve identified the mechanism. Now what’s the intervention?

Laura B

February 28, 2026 AT 12:12I’ve been using GoodRx for a year now. It’s changed my life. I used to skip doses because I couldn’t afford my meds. Now I take them every day. I didn’t know I had power until I found out I could pay $7 instead of $45.

Also, I started telling my friends. My mom didn’t know she could do this. Now she does. We’re not rich. We’re just informed.

If you’re reading this and you’re scared to ask for the cash price? Just do it. Say ‘What’s the cash price?’ It’s not rude. It’s smart. And honestly? It’s revolutionary.

One person asking. One person saving. One person breaking the silence. We’re not alone.

Robin bremer

March 1, 2026 AT 03:57bro i just found out my insulin costs $20 cash but $120 with insurance 😭 i feel like a fool

why did no one tell me this sooner??

just went to the pharmacy and paid $18 for my blood pressure pill. cried in the parking lot.

thank u op i love u

Jayanta Boruah

March 3, 2026 AT 01:40The fundamental issue lies in the absence of a centralized, transparent, and universally enforceable pricing framework. In a nation with a GDP exceeding $25 trillion, the persistence of a fragmented, state-specific, PBM-driven pricing architecture constitutes an institutional failure of the highest order.

While the empirical data presented is accurate, the proposed solutions-GoodRx, cash payments-are symptomatic palliatives. The root cause is not merely regulatory arbitrage but the commodification of essential medicines under a capitalist paradigm that prioritizes shareholder value over human health.

India, with a per capita income one-tenth that of the United States, provides life-saving generics at 90% lower cost through state-controlled procurement. The U.S. does not lack resources. It lacks moral will.

Until the federal government asserts its authority under the Commerce Clause to standardize generic drug pricing, this inequity will persist. Until then, we are not a nation. We are a marketplace.