Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation from Drug Reactions: How to Recognize and Manage This Life-Threatening Condition

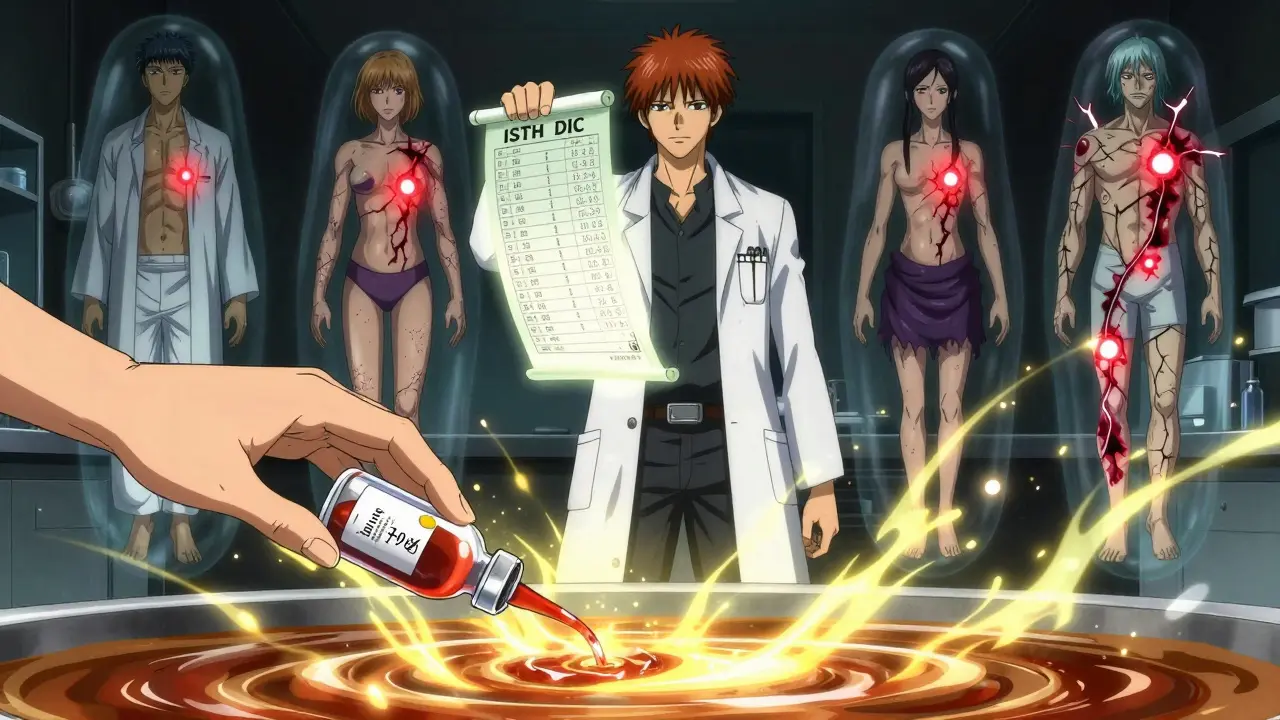

DIC Scoring Calculator

This calculator helps clinicians assess the risk of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) using the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) scoring system. Input laboratory values to determine if the patient has overt DIC or is in the danger zone.

Score Result

Recommendation: If score ≥ 5, manage as overt DIC. If score = 4, monitor closely and consider intervention.

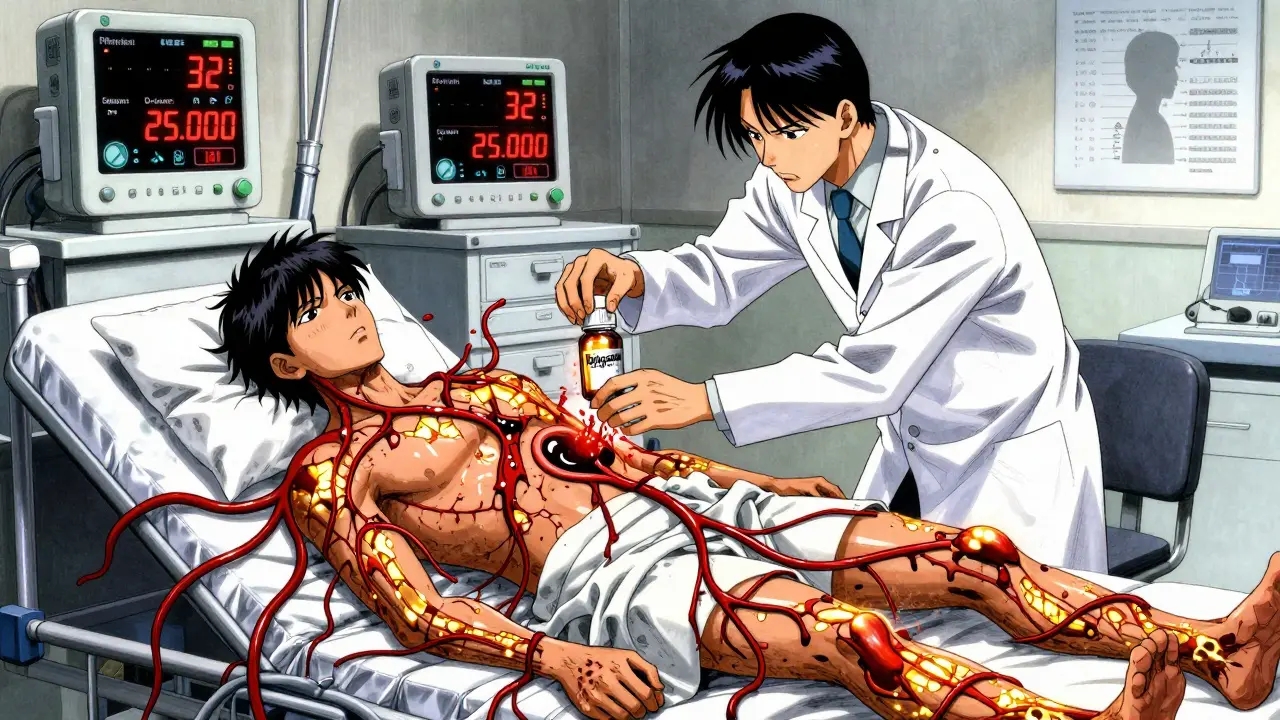

Drug-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation isn't something most people hear about until it’s too late. It doesn’t come with a warning label on the pill bottle. No one tells you that your chemotherapy, blood thinner, or even an antibiotic could trigger a cascade inside your blood that turns your body against itself. One moment you’re getting treatment for cancer or a clot; the next, you’re bleeding out internally while clots clog your kidneys, lungs, and brain. This isn’t rare. It’s deadly - and often missed.

What Exactly Is Drug-Induced DIC?

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) isn’t a disease. It’s a syndrome. A chain reaction. Your body’s clotting system goes haywire. Instead of sealing a cut, it starts forming clots everywhere - in tiny blood vessels across your organs. Those clots use up your platelets and clotting factors. Once those run out, you start bleeding uncontrollably. It’s like your blood is both freezing and draining at the same time. When drugs cause this, it’s called drug-induced DIC. Some medications directly activate clotting proteins. Others damage blood vessel walls, tricking your body into thinking there’s massive injury. The result? Chaos. According to the WHO’s global drug safety database, over 4,600 serious cases of drug-linked DIC have been reported since 1968. And that’s just what got documented. Many more likely go unrecognized.Which Drugs Are Most Likely to Trigger It?

Not all drugs carry the same risk. Some are quietly dangerous. Here are the top offenders based on real-world data:- Antineoplastic agents - Especially gemtuzumab ozogamicin (ROR 28.7), oxaliplatin, bevacizumab. These are used in cancer treatment, but they can shred your blood’s ability to regulate clotting.

- Antithrombotics - Dabigatran (Pradaxa) is the most reported direct oral anticoagulant linked to DIC. It’s supposed to prevent clots, but in rare cases, it triggers the opposite.

- Antibacterials - Vancomycin, though less common, has shown a clear signal in adverse event reports.

- Antibody-drug conjugates - Newer cancer drugs like enfortumab vedotin and trastuzumab deruxtecan have triggered DIC in multiple case reports since 2022.

How Do You Know If It’s DIC?

There’s no single test. But there’s a scoring system - the ISTH DIC score - that’s used in ICUs and hematology units around the world. It looks at four lab values:- Platelet count - Below 100 × 10⁹/L? That’s a red flag. Below 50? That’s 2 points.

- Prothrombin time (PT) - If it’s more than 3 seconds longer than normal, you get 1 point. More than 6 seconds? 2 points.

- Fibrin degradation products (D-dimer) - If it’s more than 10 times the upper limit of normal? That’s 3 points. This is often the earliest sign.

- Fibrinogen - Below 1.0 g/L? That’s 1 point. Below 80 mg/dL? You’re at immediate risk of uncontrolled bleeding.

Immediate Actions: Stop the Drug, Support the Body

The most critical step? Stop the drug immediately. No exceptions. No waiting for confirmation. If DIC is suspected and the patient is on a high-risk medication, discontinue it now. After that, it’s about supporting the body while the system resets:- Platelet transfusions - Only if bleeding or high bleeding risk. Target: 50 × 10⁹/L. If no bleeding, 20 × 10⁹/L is enough.

- Fibrinogen replacement - If below 1.5 g/L, give fibrinogen concentrate or cryoprecipitate. Below 80 mg/dL? You’re in emergency territory.

- Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) - Replaces multiple clotting factors. Used when multiple labs are low and bleeding is active.

- Cryoprecipitate - Often preferred over FFP for fibrinogen replacement because it’s more concentrated and faster to administer.

When Is Anticoagulation a Good Idea?

Most doctors assume anticoagulants are bad in DIC. But it’s not that simple. In sepsis-induced DIC, anticoagulants like antithrombin or thrombomodulin have shown mixed results. But in drug-induced DIC? The data is different. One 2019 study found that anticoagulants helped - but only in patients who weren’t already on heparin. That suggests heparin might be useful in some drug-induced cases, especially when microclots are the main problem. The key? Don’t use anticoagulants routinely. Use them selectively. Only if:- There’s clear evidence of ongoing thrombosis (e.g., new pulmonary embolism, limb ischemia)

- Platelets and fibrinogen are stable

- The drug is stopped

What Happens If You Miss It?

Mortality. Plain and simple. Studies show DIC carries a 40-60% death rate when it’s severe. In oncology patients, it’s often higher. Why? Because the underlying disease - cancer - is already weakening the body. Add DIC, and organs start shutting down: kidneys fail, lungs fill with fluid, liver stops detoxing, brain bleeds. One ICU doctor in Australia reported 12 cases of drug-induced DIC over 15 years. Mortality? 58%. All of them were on cancer drugs. Only three survived without major organ damage. In another case, a patient on bevacizumab developed DIC after the third infusion. The team didn’t suspect the drug. They treated it as sepsis. By the time DIC was confirmed, the patient had multiorgan failure. Died within 48 hours. This isn’t theoretical. It’s happening right now in hospitals.How to Prevent It

Prevention starts with awareness.- Know the drugs. If you’re prescribing gemtuzumab, oxaliplatin, bevacizumab, or dabigatran, know the signs. Check platelets and D-dimer before each dose in high-risk patients.

- Monitor early. The International Council for Standardization in Haematology now recommends weekly CBC and coagulation panels for patients on high-risk monoclonal antibodies.

- Ask the history. When a patient presents with unexplained bleeding or clotting, ask: "What drugs did you start in the last 7 days?" That’s often the missing piece.

- Update labels. Many drugs still don’t list DIC as a risk. Advocacy groups and clinicians need to push regulatory agencies to require clearer warnings.

Bottom Line: Time Is Everything

Drug-induced DIC doesn’t wait. It doesn’t announce itself. It creeps in after the third dose of chemo, after the first refill of a blood thinner, after a routine antibiotic. If you see a patient with low platelets, high D-dimer, low fibrinogen, and unexplained bleeding or clotting - and they’re on a high-risk drug - act now. Stop the drug. Check the ISTH score. Replace fibrinogen and platelets as needed. Don’t give heparin unless you’re sure it’s safe. Don’t give warfarin. This isn’t a textbook case. It’s a real, life-or-death scenario. And the people who survive? They’re the ones whose doctors recognized it fast.Can a blood thinner like dabigatran really cause DIC?

Yes. Dabigatran (Pradaxa) is one of the most frequently reported drugs linked to DIC in global adverse event databases. While it’s designed to prevent clots, in rare cases it triggers a paradoxical response - activating the coagulation cascade instead of suppressing it. Over 90 case reports exist, with many requiring emergency reversal with idarucizumab and aggressive blood product support. The risk is low, but the consequences are severe.

Is DIC the same as sepsis-induced coagulopathy?

No. While both cause similar lab abnormalities, the triggers are different. Sepsis-induced DIC comes from infection and inflammation, and the main treatment is antibiotics and fluids. Drug-induced DIC comes from a medication, and the main treatment is stopping that drug. The lab values look alike, but the management path diverges quickly. Confusing the two can delay life-saving action.

Why is fibrinogen so important in DIC?

Fibrinogen is the building block of clots. In DIC, it gets used up rapidly. When levels drop below 1.5 g/L, the body can’t form stable clots - leading to bleeding. Below 80 mg/dL, spontaneous bleeding becomes likely. Maintaining fibrinogen above 1.5 g/L is a key goal in treatment. Cryoprecipitate or fibrinogen concentrate are preferred over plasma because they deliver more fibrinogen per unit with less fluid overload.

Can DIC be reversed?

Yes - if caught early. Once the triggering drug is stopped and clotting factors are replaced, the body can often reset its coagulation system within days. Recovery depends on organ function and how much damage was done before treatment. Patients with mild DIC and no organ failure have good survival rates. Those with multiorgan failure have a 60% or higher mortality rate.

Should all patients on chemotherapy be monitored for DIC?

Not all - but those on high-risk agents like gemtuzumab, oxaliplatin, or bevacizumab should be. The ICSH recommends weekly CBC and coagulation tests (PT, aPTT, D-dimer, fibrinogen) for these patients. For others, monitoring should be based on symptoms: unexplained bruising, bleeding, or sudden drops in platelets. Routine screening for everyone isn’t cost-effective, but targeted monitoring saves lives.

Comments

Kathy Scaman

January 26, 2026 AT 21:33This is the kind of post that makes me grateful I'm not a doctor. One wrong pill and your blood turns against you? Wild. I had no idea something like this could happen from chemo or even antibiotics. Just reading this gave me chills.

Colin Pierce

January 27, 2026 AT 11:24As someone who's seen DIC in the ICU, this is spot on. The biggest mistake I've seen? Waiting for the full ISTH score to hit 5 before acting. By then, it's often too late. I always start treating at 4 if the clinical picture matches. Fibrinogen is the real MVP here-keep it above 1.5 and you buy time. And never, ever give heparin blindly. I've lost patients to that.

Timothy Davis

January 28, 2026 AT 14:11Let’s be real-this post is just a rehash of the 2019 ISTH guidelines with a few case reports tacked on. The real issue isn’t awareness, it’s that hospitals don’t have protocols for this. Most ERs don’t even have fibrinogen concentrate on hand. And why is no one talking about the fact that dabigatran-induced DIC is almost always misdiagnosed as HIT? The lab values overlap too much, and everyone’s too scared to check thrombin time. Also, ‘update labels’? Please. Pharma won’t change a word unless sued. This post is well-intentioned but doesn’t address systemic failure.

Rose Palmer

January 30, 2026 AT 03:30Thank you for writing this with such precision. As a hematology nurse, I’ve seen the aftermath of delayed recognition-patients who could’ve been saved if someone had asked, ‘What drugs did they start in the last week?’ I wish every oncology team had this checklist taped to their computers. You’ve done an incredible job distilling a complex syndrome into actionable steps. This should be required reading.

fiona vaz

January 30, 2026 AT 10:37I’m so glad this was shared. My mom was on oxaliplatin and had unexplained bruising after her third infusion. The team thought it was just low platelets from chemo. Two days later, she was in the ICU with DIC. They didn’t connect it to the drug until her D-dimer hit 22,000. She survived, but barely. This post could’ve saved her weeks of suffering. Please share it with every oncology clinic you know.

John Rose

February 1, 2026 AT 03:05Does anyone know if there’s data on whether genetic screening for clotting mutations (like the NCT04567891 trial) is being implemented anywhere? If we could flag high-risk patients before starting these drugs, we’d prevent so many tragedies. I’m not saying screen everyone-but maybe screen those with family history of clotting disorders or prior unexplained bleeding episodes? Just a thought.

Lance Long

February 1, 2026 AT 06:35Let me tell you something-this isn’t just about medicine. This is about trust. You take a pill because your doctor says it’s safe. You trust the label. You trust the system. And then, without warning, your body starts eating itself from the inside. I lost a cousin to this. He was on bevacizumab. The doctors said it was ‘just sepsis.’ He was gone in 36 hours. No one told him. No one told his family. And now? The drug’s still on the market with no warning. This isn’t just a medical issue. It’s a moral one. We need to demand better.

Howard Esakov

February 1, 2026 AT 12:40Wow, such a *basic* overview. 😒 I mean, really? You’re citing WHO data from 1968? That’s like using a 1980s textbook to perform open-heart surgery. The real insight? The 2023 EHA guidelines updated the ISTH score thresholds for oncology patients-especially for ADCs like enfortumab. And you didn’t even mention the role of complement activation in trastuzumab deruxtecan-induced DIC. Pathetic. 🤦♂️

Mark Alan

February 2, 2026 AT 17:28THIS IS WHY AMERICA NEEDS TO STOP LETTING BIG PHARMA RUN THE SHOW 🇺🇸💥 People are DYING because corporations care more about profits than labels. I’ve seen this happen in my hospital. They know. They know. And they still sell it. I’m calling my senator tomorrow. This is a crime. 🚨 #StopPharmaKillingUs

Amber Daugs

February 4, 2026 AT 14:49Of course this happens. People are just too lazy to read the full prescribing info. If you’re taking dabigatran and you’re not checking your D-dimer every week, you’re playing Russian roulette. And if your doctor didn’t tell you this? They’re negligent. I’m not saying blame the patient-but if you’re not monitoring, you’re part of the problem. This isn’t complicated. It’s just ignored.